This ultimately is the tale of two charts, and the decline in wages experienced by men is especially dramatic.Here’s the good news: Young adults who have finished college continue to earn significantly more than mere high school graduates.The gap between the median earnings of high school graduates and those with a bachelor’s degree or higher – the red versus the purple lines in the graphs above – remains wide. The difference, over a lifetime, is more than enough to justify the expense of attaining a bachelor’s degree.

Here’s the bad news: Adjusted for inflation, median earnings for young men with a bachelor’s degree or higher in 2011 were significantly lower than they were in 1971. Young women have slightly improved their position (by $630) since 1971. But as a comparison between the two graphs shows, their median is still lower than that of male high school graduates in 1971.

Much recent debate over the causes of economic inequality has focused on the extent to which technological change (robots in particular) can take the blame. But whatever the causes, the political consequences of a continuing decline in the real average wages of young college-educated workers will be momentous. It will undermine faith that a market economy always rewards effort, intelligence and skill, increasing awareness that most working people, not just those who didn’t go to college, are vulnerable to impersonal forces of supply and demand.

The causes and effects of this massive change leave a lot to unpack.

Are decreasing earnings for college graduates the effect of increasing supply? Is the market being flodded?

There is no doubt that the percentage of people attending college is now higher than it was in the 70s. But surprisingly it isn't much higher than you'd expect. From '71-79 (for men 25-34) college completion rates jumped from 20 to about 27.5 percent. For the next 10 years it actually declined, and it only recently exceeded that '79 peak. That said, it is still under 30 percent. Which, in terms of flooding the market, is pretty small.

On the other hand, college attainment for women has steadily risen over the whole period. It exceeds the attainment rate of men by quite a bit. This corresponds to the increase in women's median wages over that period. That said, college-educated women now still earn less than high-school age men in 1971. So, this isn't exactly some huge feminist victory.

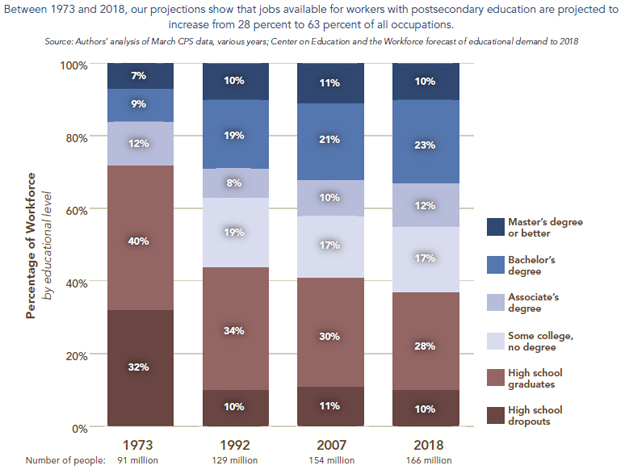

To "flood the market," you need supply to exceed demand. The exact opposite is happening. The US has a shortage in highly skilled workers for certain professions, and the need for people with bacherlor's/ higher degrees is only going to increase in the future. While the demand for people with lower education has been steadily eroding for decades. Thank computers/robots/globalization for all of that.

Addressing that problem would mean increasing the supply of college educated workers. To do that, two things need to happen: the cost of college needs to decrease, while the expected earning from a college degree needs to increase. In other words, college needs to become a better deal for more people to go. The opposite is happening, which is creating this nasty problem in US labor markets. We have a shortage in the kind of workers we need, while we have a surplus in the kind we don't need.

This is a classic example of the problem of externalities. The benefits we get from education far exceed the market price. For that reason, government is expected to subsidize the product so that its social cost and social price are equal. The library of economics and liberty explains this well.

Externalities are probably the argument for government intervention that economists most respect. Externalities are frequently used to justify the government’s ownership of industries with positive externalities and prohibition of products with negative externalities. Economically speaking, however, this is overkill. If laissez-faire—that is, no government intervention—provides too little education, the straightforward solution is some form of subsidy to schooling, not government production of education. Similarly, if laissez-faire provides too much cocaine, a measured response is to tax it, not ban it completely.This is not happening in the US right now. Most public education is funded at the state level, and the states have been cutting back. The result is far less college graduates than we actually need, while we have a surplus of lower-skilled workers.

Does your major matter? Isn't this the fault of (insert literature, philosophy, theater or whatever other liberal humanity you wish to disparage) majors?

Yes there are a diversity of earning potentials for college degrees. The Wall Street Journal does a good catalog here. But even though things like Spanish pay a lot less than things like computer science, it's a big mistake to think that Spanish is "worthless." The starting median salary for basically all degrees is higher than the mid-career median salary for people without degrees. That gap will persist throughout people's careers, irrespective of the degree they got.

This goes back to the NyTimes article and something I mentioned above. The demand for people without college education is declining at a steady clip, but the supply of these types of workers is essentially constant. You see the standard economic result: wages for these types of jobs are catastrophically collapsing. The median wage of a high-school educated man in 2011 in FORTY PERCENT LOWER than that of a man in 1971. Take a second to process that. The punishment of not attending college now is a wage that is half of what you would expect 40 years ago. Ouch.

Well if that's the case, why the hell should I deal with the misery and cost of a college education? Why don't we all go the Peter Thiel route and become entrepreneurs?

In general, it is terrible advice to tell someone to not going to college these days. Outside of a few key trades (which have their own education/ apprenticeship system), you are essentially condemning them to a life just above the poverty line (and not much better for plumbers and other skilled craftsmen; certainly worse than college grads). On the upswing, no matter what you study, even if it isn't all the way to completing the degree, your earning potential after college will be quite a bit higher (big caveat: just don't bury yourself in debt).

Now, despite all my liberal inclinations, poverty in the US is not so bad (certainly better than in the 70s when the war on poverty began), and it is actually getting better. But this has everything to do with the those entitlements that the right despises. Without significant redistribution of money to the poor, things would be pretty bleak (even bleaker than this). In other words, because of pressures in the labor market, we are essentially forced to implement a form of light socialism in order to make life in America bearable. Think about Walmart and McDonalds workers on food stamps. There's a lot of them, and they typify America's low wage problem.

|

| From the Atlantic Cities Blog. |

That's all great. I'll send my kids to college. Considering where we started in the beginning, what have we learned today?

It's quite exciting to know how much we can glean from what is a relatively simple statistic. But here's some bullet points:

- We need to increase college graduation rates in America.

- To do that we need more kids going to college (which depends almost exclusively on getting kids out of poverty).

- We need to make college less expensive (which is related to public funding)

- We need to increase the amount of money earned for a college degree

- Ideally, growth in wages should track with growth in GDP/ productivity (this stopped about 20 years ago, once income inequality started becoming a real problem).

Your other alternative is giving low-wage workers the ability to negotiate higher pay (through unions) or mandating higher pay (through national wage standards). Ultimately, though, both of these are redistributive policies (which is why conservatives aren't very fond of them).

This gets us stuck in the wage problem that started this whole conversation. Even if you don't want to create policies for redistribution to the middle class (or redistribution to expand the middle-class), you're stuck with redistribution to mitigate the problems for the expanding poor. For Republicans, you'll need to redistribute to middle class now or redistribute to the lower class once the middle class fully collapses. It's a really shitty choice. I apologize.

Subsidizing the middle class might not be the worst thing to have ever happened. Thomas Friedman isn't exactly Lenin, but he sees a strong incentive for some form of universal economic baseline, one that encourages people to aspire for more. You give everyone a social bottom line, and you expect them to compete from there. This still allows for inequality, but it is more fair in the sense that everyone at least gets to keep by essentially the same rules.

There is an economic concern here too, if we ultimately decide to not subsidize the middle class (through redistribution, wage hikes, unions or all of the above). Is this weird labor market dynamic good for long-term growth? Probably not. Is it good for society and political outcomes? Definitely not. There are more than a few "people's revolutions" that attest to that.